Global CdTe PV manufacturing capacity is currently around 20 GW DC, but it can expand to 100 GW DC by 2030, says a new DOE-backed study

While the world’s cadmium supply is sufficient, tellurium constraints could be eased through better recovery from copper refining residues and improved extraction from existing supply chains

Thinner absorber layers, reduced tellurium use per watt, and efficiency gains will be key to improving CdTe competitiveness with silicon modules

A study by the US Department of Energy’s National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR) says global cadmium telluride (CdTe) manufacturing capacity could reach 100 GW DC by 2030.

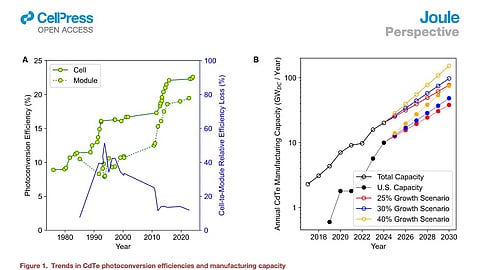

The study notes that CdTe PV manufacturing capacity has expanded at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 37% since 2017. At this rate, it could reach a cumulative capacity of 100 GW DC by the end of this decade, supporting multi-TW DC-scale deployment by 2050.

The only PV technology besides silicon producing solar modules at the GW scale, CdTe’s global annual manufacturing capacity stands at about 20 GW DC. It was once considered niche due to the limited availability of tellurium (Te), but this is no longer the case. US-based First Solar, the world’s largest producer of CdTe modules, alone targets a 25 GW annual nameplate capacity by 2026 globally, including 14 GW in the US (see First Solar’s 3.5 GW Louisiana Solar Module Fab Online).

According to the research, there is no dearth of cadmium (Cd) availability, as it is readily available as a byproduct of the Zn mining industry. Improving the availability of Te is possible through enhanced extraction from existing supply chains.

Most tellurium (Te) supply comes as a byproduct of copper mining, but only a small share is recovered, with most lost to tailings. Recent developments indicate that improving Te recovery during copper refining, especially from anode slimes, is possible.

Notably, China has imposed export controls on tellurium supply along with a number of other critical materials (see China Announces Export Controls On Cadmium Telluride).

Another improvement suggested by researchers is thinning the absorber layer. CdTe modules currently use copper-doped CdSexTe1-x absorbers, but the industry is moving toward Gr-V doping. Using thinner absorbers could increase CdTe manufacturing capacity with the existing tellurium supply, while also reducing processing time and capital costs.

First Solar’s CdTe cell with Gr-V doping technology and Cd(Se,Te) alloyed absorber holds the record high efficiency of 23.1%. However, there is still room to improve the overall efficiency of these cells and modules, especially in relation to FF and open-circuit voltage (Voc).

Future research work should focus on improving tellurium recovery from copper refining residues, reducing losses during copper processing, and exploring tellurium-rich deposits associated with other metals such as gold and lead.

Scientific efforts should also focus on increasing module efficiency and reducing the amount of tellurium used per watt, the writers recommend. Higher efficiencies would make CdTe modules more competitive with conventional silicon modules.

“Both scientific and supply chain innovations will be necessary to maintain the high CAGR of the CdTe PV industry and cement it as a key part of the pathway to multi-TW scale PV deployment,” reads the study that includes participation from members of the Cadmium Telluride Accelerator Consortium, established by the DOE in 2022 (see US Laser Focused On Silicon Free PV Technology).

Titled Roadmap to 100 GWDC: Scientific and supply chain challenges for CdTe photovoltaics, the study has been published in the scientific journal Joule.