Key takeaways:

Resiliency, as presented in the talk, extends beyond risk mitigation to include identifying opportunities under persistent uncertainty

PV sector risks span supply-chain dependence and climate-related disruptions, both of which influence the financial decision-making

Linking solar with agriculture, buildings, water systems, and circular-economy practices offers expanded roles for PV beyond power generation

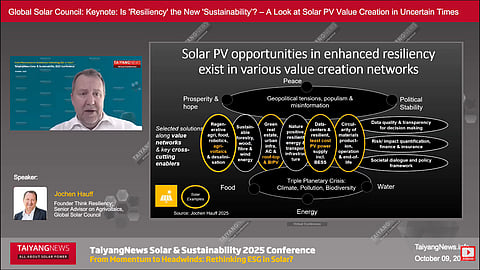

Jochen Hauff, founder of Think Resiliency, opened the TaiyangNews Solar & Sustainability Conference with a framing of today’s global context of sustainability. He described a ‘triple planetary crisis’ for food, water, and energy, which are impacted by climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss, combined with intensifying geopolitical tensions, unstable supply chains, and rising social pressure. Hauff said that this ultimately threatens both economic prosperity and political stability. Drawing on public statements by senior financial leaders from Europe, he highlighted that the financial sector increasingly views climate and geopolitical risk as a direct threat to investment performance, system resilience, and even long-term economic viability.

Hauff argued that the concept of resiliency must extend beyond traditional risk mitigation. In his view, resilience involves not only understanding and managing risks, but also proactively identifying opportunities arising from uncertainty. He emphasized that uncertainty is not short-lived but is likely to persist or intensify.

For the solar sector, he identified 2 categories of risk: supply chain risks and climate-related risks. Under supply-chain risks, he noted the dependence on a narrow set of manufacturing locations, exposure to sanctions, cyber threats, and workforce constraints. The climate risks include extreme weather, insurance challenges, operational disruptions, and long-term asset devaluation. Financial institutions are increasingly integrating these risks into investment decisions, meaning that climate exposure can affect project bankability well before an actual event occurs.

Despite these pressures, Hauff stressed that significant opportunities emerge when solar companies move beyond narrow value-chain thinking to what he called value networks. Examples include combining solar with agriculture (agrivoltaics), and water-management solutions to stabilize farmer income while improving food-system resilience; integrating PV into buildings (BIPV) and urban environments for cooling, shading, and grid relief; linking solar with air-conditioning demand; powering data centers that will continue relying primarily on wind and PV; and supporting circular-economy approaches that begin at the design stage, extend through maintenance and repowering, and treating recycling as a last resort rather than the first response. Such models, he argued, expand the relevance and economic value of solar well beyond electricity production alone.

Hauff also highlighted the need for a shift in sustainability narratives. Rather than framing sustainability primarily as something done for future generations, he suggested emphasizing its immediate relevance for today’s livelihoods, retirement security, and societal stability. He argued that this is necessary because the political window for ambitious sustainability policies may be narrowing amid rising populism and geopolitical strain. He concluded that resiliency is not a replacement for sustainability but offers a complementary lens that stress-tests sustainable systems, anticipates ongoing uncertainty, and supports stronger long-term outcomes.